Timelessness & A E S T H E T I C S

- OSC

- Oct 12, 2020

- 12 min read

Updated: Jun 13, 2024

I work predominantly in the Retrowave genre of music and therefore focus heavily on crafting sound palettes and musical aesthetics reminiscent of the 1980s (as well as the late 1970s and early 1990s). I'm not alone in doing this as there are countless other artists working under the umbrella of the Retrowave aesthetic (Synthwave, Outrun, Vaporwave, etc). It's a vibrant community with some brilliant personalities and fantastic music (and art).

The notion of aesthetics (or " A E S T H E T I C S " as they're commonly referred to in the Retrowave scene) are broad and varied. Some artists look to simply make music that sounds exactly like it did in the 1980s (which is an aesthetic specifically tied to an era of the 20th Century musical canon), whilst other artists take a more nuanced approach and look more broadly at other aspects of culture from this period to create a slightly different aesthetic experience; one that views the 1980s through a contemporary lens, and in some cases creates music that sounds more 1980s than the music of the 1980s itself.

In this article, I'll examine a couple of artists who I believe craft a musical aesthetic that goes beyond the musical inspiration alone and takes into account broader influences and aspects from various cultural inspirations (not just music).

Is Retrowave About Making Music Sound Like It Did In The 1980s?

Well... yes and no! Music is often strongly defined and identified by the era (usually the decade) in which it was created. For example, whether you're listening to Otis Redding, The Beatles or Simon & Garfunkel, you're listening to the 1960s. Whilst later generations clearly borrow significant inspiration from the 1960s, they don't ever truly sound like they could be mistaken for records from the 1960s.

On the contrary, some Retrowave music really can sound as if it's straight out of the 1980s, yet it's been produced in the 2000s or the 2010s. In this respect, I think that Retrowave is rather special and unique; achieving something that other homage-based musical styles haven't. However, there's also an argument that some music within the Retrowave scene is not actually like the music of the 1980s and instead is more of an aesthetic sleight-of-hand.

Let's explore this notion with one of the most highly regarded artists in the scene: Mitch Murder.

Mitch Murders The Competition

Mitch Murder is one of the most well known Retrowave artists. His production quality and aesthetic is powerfully on-point with the Retrowave movement. However, like many of the top Retrowave artists (The Midnight, FM-84, Droid Bishop, etc), I believe this retro aesthetic is arguably a sophisticated game of musical smoke and mirrors.

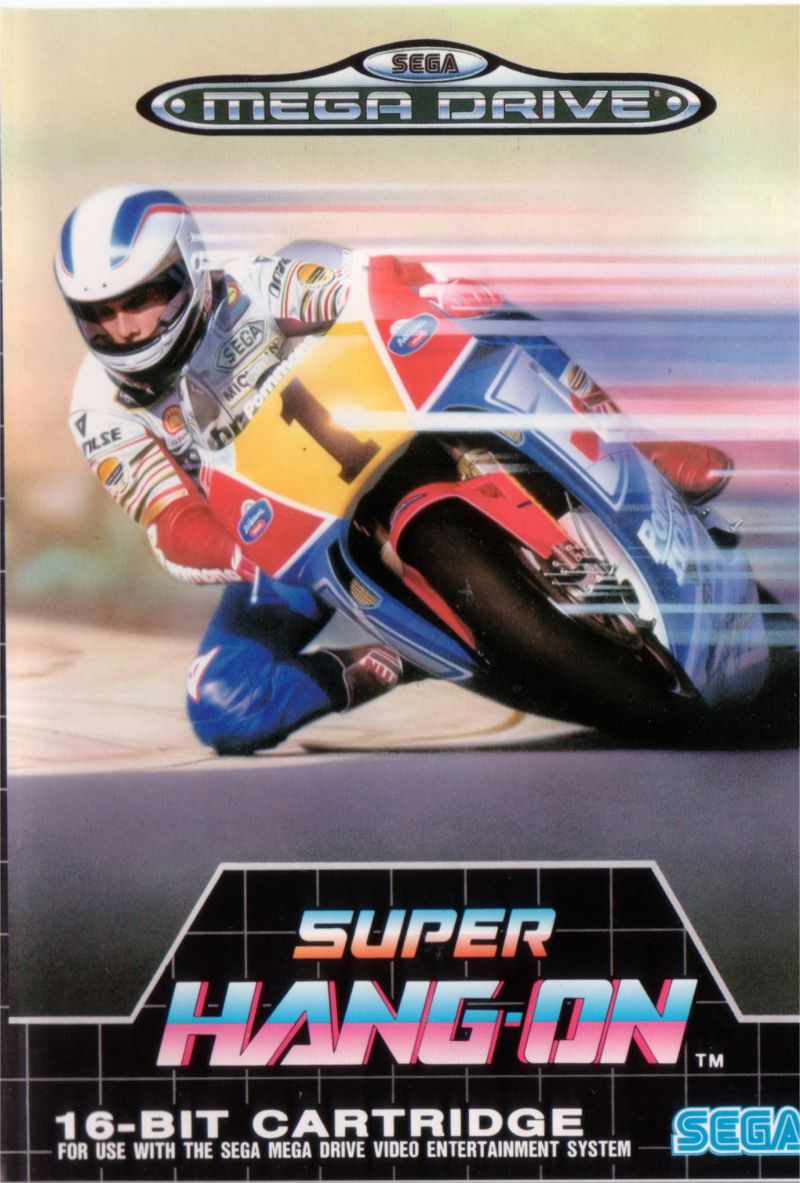

For example, Mitch's cover of Outride a Crisis from the video game Super Hang-On (originally from 1987); you can listen to the song here. When I first heard this, I was awash with nostalgia for my childhood and playing this game on my older brother's SEGA Mega Drive. I'm confident that I'm not the only person who will have had this sort of nostalgic experience upon listening to this cover version.

The FM-Synth bass; the FM-Synth, bell-heavy electric-piano; the super-tight, punchy snare and kick drum; the delicate white-noise hi-hats; the delicious, spacious reverb on the synthesised tom fills; the cutting FM-Synth lead; the driving rhythm and ghosted snare fills; I could go on.

Mitch's cover encapsulates everything about 1980s synthesised sound design I thought I remembered fondly from childhood and presented it with glorious high-fidelity, in a production tone that is warm, soft, airy and spacious; much like a well mixed 80s album like Toto IV or Tango in The Night. Mitch's cover version is, or so thought, exactly how I remembered it sounding on the original game that I last played at the age of six, back in about 1990.

Spurred on by Mitch's cover, I decided to listen to the original version on YouTube and... Oh!

Whilst the original composition and arrangement are wonderful, especially given the technical limitations of the technology needed to play the music (the Yamaha YM2612 synthesis chip used by SEGA at the time), it is rather dull in timbre, the mix is rather one-dimensional and doesn't have any of the aesthetic excitement or sparkly high fidelity and warmth that Mitch's version has. It left me both underwhelmed by the original and even more respectful of Mitch's recreation.

What I believe Mitch captures so perfectly with this cover version is to recreate an iconic video game theme, not as it was, nor in a modern or contemporary fashion, but rather in the way that those of us who last experienced the game 30 years ago distortedly remember it sounding, through our nostalgic, rose tinted lenses. I.e. he didn't make it as it was but he did make it as we romantically remember it.

One Aesthetic to Rule Them All

Memories and nostalgia are funny things; highly subjective and can be very distorted from the realities of what actually happened. Furthermore, the mind can sometimes vividly remember things that simply didn't happen, as widely documented by The Mandela Effect. I can't pretend to know much about psychology or how memories work, however talking purely from personal experience, I realised my mind had jumbled up several different aesthetics from my childhood into one collective (imagined) aesthetic; the one aesthetic to rule them all:

The sound of this, and other early 16-Bit video-games, experienced for the first time as a child

The FM-Synthesis sound palette that was subconsciously, continually fed to me through TV and film soundtracks, pop-music and video-game soundtracks as a child

The warm and dynamic production aesthetic of 80s platinum selling records consumed on my family's high-quality Sansui separates HiFi system (a typical, good quality, 1980s HiFi); warm, deep, soft, rich, with a delicate and never harsh top end

I feel the above bullet points (and probably other stimuli from the era also) have somehow bound together to form an idealised (hyper-real) imagining of my nostalgic experience, and it's this that Mitch manages to tap into with his version of Outride a Crisis from Super Hang-On.

With the above in mind and having digested literally all of Mitch Murder's releases alongside countless video-game and movie soundtracks from the 1980s, alongside countless pop hits from the era, I've come to the conclusion that: whilst Mitch is unmistakably reminiscent of the 1980s and obviously draws from the 1980s as a source of inspiration, it would be a disservice to simply say his music sounds like music from the 1980s. The aesthetic experience of Mitch Murder is a much deeper and more sophisticated one. It's the whole of the 1980s as experienced through youth and then nostalgically remembered as an adult, condensed into a musical form.

The tonalities, tropes and stylisations of his music are huge exaggerations and embellishments of trends, themes and tropes of the 1980s. The themes of his songs, the sound palettes he uses, his choice of cover versions and the artwork he uses for his releases are all steeped in 1980s sentiments that go far beyond just the music. In culmination it could be argued that he sounds more 80s than the 80s did! Something most likely only achievable with decades of retrospective reflection, analysis and probably some first-hand nostalgia from having been a young child during the era that's now being romanticised by the music.

Outside of Time & Timelessness

With Mitch seeming unmistakably 80s, yet also more 80s than the 80s itself (and having released his work 20-30 years after the 80s), one could infer that future observers might find it difficult to pinpoint him to a specific time-based aesthetic (such as how music can easily be identified as 60's or 70's music). In this regard, his work would exist outside of conventional timeline chronologies. It has become Timeless.

In a blind test conducted 100 years in the future, would musicologists be able to accurately pinpoint when Mitch Murder's music was made? It could potentially be the cause of much debate; is it, or is it not from the 1980s? Some might argue it is, on account of how it embodies all of what the 1980s is about, whilst others would argue it's too perfect and too pure an 80s experience and must be some form of retrospective homage or pastiche made long after the 80s had transpired.

I'll See Your Mitch Murder and Raise You Tom Waits

Whilst thinking about how Mitch's work might exist outside of conventional time-period categorisations, it occurred to me that another musical love of mine, Tom Waits, also inhabits this no-man's-land of musical timelessness. Having been active since 1973, there's a lot of things that could be discussed, but to keep things simple, I'll just focus on his work from the 1970s.

Tom Waits For No Man

About 18 years ago I was shown Closing Time, the 1973 debut album by Tom Waits. A beautifully crafted album of soulful, singer-songwriter pieces that had part jazz, part country and part folk inspirations. It's a strong album, typical of the singer-songwriter style of the early 1970s. I enjoyed it so much that I began to work my way through Waits' discography (in chronological order), purchasing an album every two or three months (this is before music had found its way into every corner of the Internet and become so easy to procure).

About six albums into this exercise (around Waits' 1978 album Blue Valentine) it occurred to me that whilst Waits' early albums sounded quite appropriate for the 1970s, by the mid-late 1970s he didn't sound like a 1970s artist anymore. The lyrical themes and musical stylings harkened back to a bygone era of Americana that lay somewhere between Jazz clubs and seedy bars of 1940s California and Jack Kerouac's poetic descriptions of the underbelly of 1950s America.

I was however already familiar with much Jazz from the 1940s and 1950s, I was keenly aware that Waits' music didn't really sound like Jazz from the 40s or 50s. Furthermore, whilst his lyrics were reminiscent of these decades, they rarely, if ever explicitly set themselves in that time period by claiming to be in the 1940s or 1950s. Yet without doubt, the music took my imagination to these times and places, and (like Mitch Murder's exaggerated, over-the-top reimagining on the 1980s production style) it wasn't a coincidence.

Aesthetic Themes, Aesthetic Tropes

What Waits had achieved with albums like Nighthawks at The Diner, Small Change, Foreign Affairs and Blue Valentine was to make something more 1950s than the 1950s actually was.

Lyrics would allude to locations, famous people, scenarios, movies, TV shows, radio and billboard advertisements, specific cars, etc, that whilst still part of pop-cultural knowledge in the 1970s, were all extremely evocative of the late 1940s and early 1950s. He'd couple this lyric writing with chord progressions and melodies that hinted at musical tropes from The Great American Songbook, blending traditional Jazz and blues sentiments with lush orchestration the likes of which one would expect to hear in a Hollywood movie or Broadway musical of the 1940-1950s. It's worth noting that, born in 1949, he's mentioned in interviews that movies and music from this era were a big part of his upbringing; more so than the 1960s explosion of the youth pop culture. I.e. he had first hand experience of consuming this music via his parents' record collection and therefore a strong and fond nostalgia for the era.

These albums had a lot of orchestration and were produced by the legendary Bones Howe who recorded the orchestras in some of the same studios used for Hollywood movie scores. This gave the orchestra's a tone and character evocative of cinematic orchestration of old (especially so given the aforementioned composition techniques that harkened back to The Great American Songbook).

All together, Waits was crafting characters and stories from a bygone era through nostalgia and hindsight, coupled with instrumentation and production that was (mostly) period correct and evocative of older music and cinema scores of the era in which the stories appeared to be set.

Whilst this can be seen as the ingredients of homage or pastiche, (like Mitch Murder) the sheer unique quality and artistry with which it is done means Waits' music goes far beyond that of mere pastiche and is able to stand on its own two feet; to be regarded as it's own aesthetic; its own art-form.

Like Mitch and the 1980s, Waits' music bares the hallmarks and character of a bygone era, but presents this era through an entirely new and contemporary lens. Through this approach Waits gives a distinctly 1970s, socially-conscious voice to societal issues of the 1950s such as down-and-outs, bums, drunks, prostitutes, drug-addicts, criminals and more; addressing such topics in this explicit and gritty demeanour was not typical (maybe not even socially acceptable) during the 1940s or 1950s.

By playing with different decades of history in this way, he creates an aesthetic that exists outside of these very same decades he's toying with. He sounds both 1940s/1950s and 1970s, whilst paradoxically not sounding like any of them. It is in this way that I believe his music (like Mitch Murder's) had become outside of time or timeless, and is a masterclass in aesthetic design.

I'll leave Waits here for now, but rest assured that whilst his musical output took many twists and turns through the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, his dedication to remaining outside of trends and bringing exaggerated, expanded and sometimes outright surreal stylings of bygone eras continued. Later output would sometimes hark back to new frontiersmen, 19th Century eastern European folklore, the industrialised late-1800s, the early 1900s, and more. It's hard to describe, but the proof is in the listening! I believe it's some of the finest musical output the 20th Century has to offer and it's well worth a listen. I guess, it's sort of like if the Steampunk art style were music, but I digress...

What Can Mitch & Tom Teach Us?

Natsukashii is a Japanese word that crudely translates to nostalgia, however we don't have a truly accurate equivalent in English. It's a more nuanced word that refers to the warm, sentimental feeling one gets when they experience nostalgia. Moreover, whilst nostalgia typically centres around specific memories of places, objects, people or times that we ourselves have experienced, it's entirely feasible to experience Natsukashii about a feeling and it can refer to an imagined or idealised time or place. I.e. it's the happiness or yearning (sometimes sombre or melancholy) brought on by remembering a good time and one can feel Natsukashii for a time or place they've never actually experienced, but can feel nostalgic about nonetheless.

Let's consider Natsukashii in relation to genres such as Vaporwave and Futurefunk in which low fidelity and worn out cassette-tape effects are used in music to invoke nostalgia. This is a style of music that is hugely popular with the 18-24 year-old demographic; an age group arguably too young to have grown up with cassette tapes as their primary source of media. Furthermore let's consider how Lo-Fi Hip-Hop will often use vinyl crackle and other ageing effects to similarly invoke Natsukashii, again a style of music popular with people arguably too young to have consumed music on vinyl.

The overarching theme in these styles of music is Natsukashii; the heartwarming feeling brought on by the blurring of nostalgia and sentimentality experienced whilst consuming particular forms of music.

Returning to Mitch Murder and Tom Waits, I would suggest that knowingly or otherwise, both are masters in crafting Natsukashii in the minds and hearts of the listener. Both use vastly exaggerated tropes and hallmarks stylised through a modern, retrospective lens, giving a new voice to old ideas in order to craft and create an enticing sense of euphoria for eras that the listener often won't have any experience of.

Natsukashii & Timelessness in Retrowave

Encouragingly, whilst music designed around principles of Natsukashii was uncommon in the past, thanks to the boom in DIY music producers and a thriving Retrowave scene, I believe we're now seeing many people master these techniques and release a slew of good quality and enjoyable music that presents itself primarily on notions associated with Natsukashii.

In this era where Natsukashii is (knowingly or otherwise) the prominent theme in Retrowave output, the ability to pinpoint a song's release based purely on its production aesthetic is likely to become ever harder (and perhaps irrelevant); an era in music that's time-period is indiscernible; an era of music that will always be relevant and/or relatable; an era of music that is outside of time; an era of music that is, by its very aesthetic, timeless.

So What...?

It's important to stress that these are merely my personal musings on the boom in nostalgia based music, and that there are not explicit tips and tricks to be gleamed from this discussion; more that of an overarching philosophical approach. I believe we can examine, learn from and follow the lead of artists like Waits and Mitch and consider the potential for Natsukashii in our own music (regardless of genre). It's important not to simply craft homage or pastiche to our inspirations, but to go further and condense everything we know, believe, understand and remember from different periods of time and lend a new musical voice to these collective memories (and feelings); new music born of non-musical memories and experiences.

Furthermore, we can take heart and inspiration from this movement of Natsukashii infused aesthetics as it has great potential to give new life to musical forms and styles that might otherwise be considered hackneyed or out of fashion. By reframing aesthetics in the guise of fondness and/or reflective sentimentality, both creators and consumers free themselves of stigma (of liking things once they become unfashionable). Furthermore, it ensures a wide and diverse sound palette remains in the musical canon and social conscience of the listener, resulting in a culture of absolute creative freedom and experimentation as artists combine older and new musical stylings, freed from the shackles of trends and fashion. An environment in which aesthetics rule all, boundaries are pushed beyond expectation and the past, no matter how "cheesy", is never disregarded.

Keep it retro ;-)

.png)